The U.S. Agency for International Development has deployed a disaster response team to Ethiopia, where there is a “crucial window of time” to avert the worst impacts of a drought, according to the agency’s disaster chief. The disaster assistance response team — or DART — traveled to Ethiopia on March 3.

El Nino-induced weather extremes are wreaking havoc on livelihoods, food and water systems across Ethiopia. While the situation has yet to escalate into a full-blown famine, the current drought is considered worse than that which contributed to the devastating 1984 Ethiopian famine, which — together with human rights abuses — killed roughly half a million people.

USAID’s DART teams are better known for mobilizing in the wake of a catastrophic event — dropping into Nepal’s post-earthquake rubble, for example, or scrambling to save lives in the aftermath of a typhoon.

In this case, they will take on a more preventative role. With El Nino’s worst impacts still looming in East Africa, USAID hopes the DART can leverage its logistical and personnel capabilities to set up a “series of firewalls” that prevent people from losing what they have, said Jeremy Konyndyk, director of the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance.

Read more stories on disaster response:

"With the announcement of the DART, we are acting to prevent a major humanitarian crisis and protect Ethiopia's hard-earned development progress," said USAID Administrator Gayle Smith in a statement at the time of the deployment.

Many of USAID’s development programs have “emergency modifiers” built into them, Konyndyk said. These allow for extra emergency funding to flow to a country if an emergency occurs, in order to protect the development investments USAID makes around the world. “That’s a practice we’re now using quite broadly within our resilience programming,” Konyndyk said.

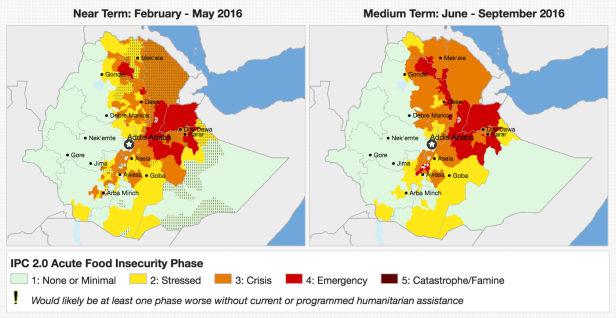

“That has all helped, but we saw the numbers continue to grow and the crisis continue to worsen,” Konyndyk said. “The launch of the DART was a recognition that there was a need for a further surge of support to prevent potentially catastrophic outcomes over the summer … We still have a crucial window of time over the next few months.”

The “firewall” model Konyndyk described involves a series of interventions to prevent a series of cascading negative impacts. To prevent livelihood loss, USAID provides seed and livestock investments for farmers. When people cannot support themselves, the agency provides food aid to prevent malnutrition. And when moderate malnutrition occurs, the agency intervenes with acute malnutrition treatment. The idea is to stop that chain at its earliest point in as many instances as possible. Getting on top of the situation before it deteriorates makes that more likely.

“This is a crisis. There’s no question, and it’s going to be a big challenge. But whether it devolves into a catastrophe in terms of human impact, that’s what we’re trying to avert,” Konyndyk said.

There is some light at the end of the tunnel, the aid official said. The next rainy season is projected to be “fair, if not good,” and that means that if USAID is successful in building out its seed distribution networks, the next harvest cycle should be good enough for farmers to start reversing some of the downward trends.

But for that to happen, USAID needs to devote resources and attention to the crisis now, not after it has deteriorated into something much worse, he said. And without the news hook of a full-blown catastrophe to point to, it is not always easy to compel public — or budgetary — attention. That is “ironic,” considering that with slow onset crises there is often a greater opportunity to save lives than when there is with sudden, catastrophic events, Konyndyk said.

“In a natural disaster — an earthquake or a typhoon — most of the people who are going to die or be severely affected have already been affected by the time the media coverage starts,” Konyndyk said.

“A crisis like this — which we can see coming — that early awareness and early resourcing is crucial, because the lifesaving potential is much, much greater, even though the crisis itself is not always as sexy.”

Read more international development news online, and subscribe to The Development Newswire to receive the latest from the world’s leading donors and decision-makers — emailed to you FREE every business day.

No comments:

Post a Comment