Tekle Birhan clutched her malnourished infant son as she waited to get a food supplement and treatment at an Ethiopian health clinic in early December. It was their third trip in as many months to the facility, located about an hour’s walk from her family farm that has seen almost no rain since July.

The worst drought in 50 years is eroding harvests of everything from corn to sorghum across Ethiopia, compounding a food shortage for a country where 30 percent of the population subsists on less than $1.25 a day. Already sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest wheat consumer, Ethiopia will need $1.1 billion to buy food for more than 18 million people this year, according to a report by the government and humanitarian partners including the United Nations.

“Because of the drought there is crop failure, so we don’t have any food," Tekle, 30, said in an interview at a packed clinic in the Hintalo Wejerat district of the Tigray region. As her 18-month-old son nibbled on a cookie, Tekle said that the pulse, barley and wheat crops on her family farm got almost no moisture in July, and the normally wet month of August was dry.

Ethiopian droughts have become more frequent and severe in the past decade, and a lack of rain from El Nino weather patterns is fast becoming a problem in many parts of Africa. Zimbabwe, Zambia and South Africa have reported failed corn crops. Ethiopia, among the world’s poorest countries, will see the number of people that need food aid almost double this year. The nation has historically struggled with hunger, including in the 1980s, when famine and civil war left hundreds of thousands of people dead.

Bigger Purchases

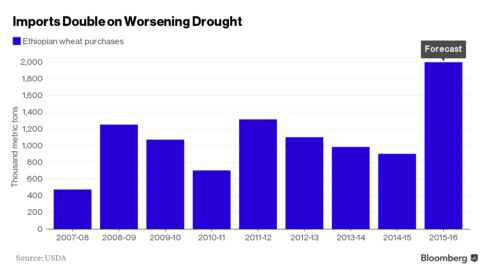

Ethiopia, which is the continent’s most-populous nation after Nigeria, is already buying more grain, purchasing 1 million metric tons of wheat in a tender announced in October. That’s about the same as it usually procures in an entire season. The country will need about another 500,000 tons in the next few months to replenish stockpiles, said Qaiser Khan, program leader for the nation at the World Bank, which is helping fund the grain purchases.

Farmers in Ethiopia usually harvest two grain crops a year, and problems started during the smaller “belg” season, when rains were about half the average from March to May. Erratic precipitation throughout the summer mean that the main “meher” harvest in most eastern areas also will be well-below average, according to the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network. The country is normally Africa’s third-largest grain producer, after Nigeria and Egypt.

“It’s a really scary situation,” Mario Zappacosta, an economist at the UN’s Food & Agriculture Organization, said in an interview from Juba, South Sudan. “In part of the country, there were two bad seasons in a row.”

Ethiopia, with almost 97 million people, is just finishing up the harvest in some drought-hit areas, so shortages will probably be most severe from March or April, when stockpiles are depleted, Zappacosta said. Wheat imports into the nation will more than double to a record 2 million tons this season, the U.S. Department of Agriculture forecasts.

Food Aid

Near the border of Ethiopia’s low-lying, arid Afar region, Abraha Haftu, 39, said he is facing a dry rainy season for a fourth year, and water shortages are adding to a lack of food supplies. Faced with crop failure, his family will once again have to count on the Productive Safety Net Program, an aid project run by the World Food Programme, he said.

“Water is very critical, as well as food," he said, waiting in line at a government food-distribution warehouse in Hintalo Wejerat. "The government is trying, but some of the water sources are dry."

Dried-out pastures have also killed off livestock, with 200,000 animals estimated to die in 2015 and an additional 450,000 this year, according to the UN. That’s helping push up the food-import bill, putting more strain on the country’s already depleted foreign currency reserves, said Clare Allenson, an Africa-focused analyst at Eurasia Group, a Washington-based research and consulting firm.

“There’s already a lack of dollars available to the private sector,” Allenson said. "The livestock sector is really suffering, the same for milk and vegetables. This has led to major food-price inflation."

Improved Defenses

Ethiopia has improved its defenses after previous famines. Better infrastructure, a growing economy, access to international aid and years of peace mean the country is more prepared to cope with crop failures than in the 1980s, FAO’s Zappacosta said.

The amount of international aid dollars available this year is likely to be stretched, with many crises cropping up around the world. The UN and humanitarian agencies released an appeal last month for a record $20.1 billion in funding, citing crisis situations in 27 countries.

“There are so many other emergencies in the world, and donors will have to decide where to put their money,” Zappacosta said. “There is some doubt that Ethiopia can pop up as a priority when you have Syria, South Sudan, Central African Republic and many other places in the world in bad situations.”

No comments:

Post a Comment