Hope in a Changing Climate - YouTube: ""

'via Blog this'

Friday, February 21, 2014

Sunday, February 9, 2014

Shelton couple helping women in Ethiopia break the cycle of poverty | Shelton Herald

Kim Barbosa and her husband Joel with Fikiraddis, a teen from the African country of Ethiopia whom the Shelton couple has sponsored.

Kim Barbosa watched a video online about a community in Ethiopia that had to find the basics for survival out of a trash can.

“It was just heartbreaking,” said Barbosa, 29, of Shelton.

During the past two years, she and her husband, Joel, have visited the country twice, have sponsored a child there, and are working toward funding a program for local women to learn a trade.

Helping them get a trade, Barbosa said, will make life easier for the women and children of Entoto Mountain.

“We traveled to Ethiopia the last two summers,” she said.

Sponsoring a girl

Before heading with her husband to Ethiopia, a nation in eastern Africa between Kenya, Somalia and Sudan near the Red Sea, Barbosa reached out to a nonprofit agency, Ordinary Hero, which facilitates sponsoring children in the country.

Through the group, she was able to sponsor a little girl, Fikiraddis, who was about 11 years old in 2011.

While preparing to go overseas, the Barbosas were able to send letters and packages to Fikiraddis by way of Ordinary Hero.

Meeting Fikiraddis

For part of the mission trip, the couple volunteered to help women with HIV. When the husband and wife went to the village where their sponsored child lived, another child ran off to find Fikiraddis.

She didn’t know the American family was coming to meet her.

“The coolest thing when we met her … she pulled out the photo we sent her … [it was] amazing,” Barbosa said.

An Entoto woman carries firewood on her back during a 20-mile trek on the Entoto Mountain, Ethiopia. The typical pay is a $1 a day. Kim Barbosa of Shelton wants to help these women learn a trade so they could better support their families.

“We went over again this past year and were able to see her again,” she said. “We feel like she’s part of our family.”

Addis Ababa, the capital of Ethiopia, was a mix of rich and poor, with makeshift homes on the sidewalks and well-dressed people walking around them.

“The most surprising thing was you would see a very stark contrast” in people’s economic circumstances in the capital, Barbosa said.

Returning back home

Barbosa was full of mixed emotions upon returning to the United States. “I felt like I didn’t help anyone,” she said. “Anybody could go to Ethiopia.”

But she’s now making strides to help raise awareness about the situation.

She and her husband show slides of the children they met in Ethiopia to the children at St. Joseph’s Church in Shelton in the hope they can inspire more people to help those in need.

Entonto Mountain

The second time the Barbosas went to Ethiopia, they met a man named Endihnew. He works at Entoto Mountain, Ethiopia, under his group called Endihnew Hope.

“He started the organization five years ago and was relying on donations from family and friends during that time,” Barbosa said.

Each Saturday, Endihnew Hope helps feed the children of the Entoto women who have to walk nearly 20 miles round-trip up a mountain to bring home heavy piles of firewood. They are paid the equivalent of about one U.S. dollar a day.

“They just started swarming” for food on the day that Barbosa witnessed the organization at work, she said. Endihnew ran out of food to feed the children on that day.

She and the group she was with then went through their bags to pull out whatever food they had to give to the children.

Helping hands

“Two of my teammates and I began advocating for his organization since returning home this past summer,” Barbosa said. They set up a Facebook page, Facebook.com/EndihnewHope.

“My husband, Joel, is a graphic designer and designed the logo which is on the Facebook page,” she said.

A woman in Ethiopia carries a heavy load of firewood.

Barbosa hopes to raise $4,100 to get a program up and running to teach the women who make the long journey up that mountain daily how to create items from clay.

The $4,100 will pay for a trainer for the women for three months, a year’s rent for a building, land to make the fires over which the pottery can be made, a salary while they are training, and materials and eight pottery wheels.

Breaking the cycle

These jobs won’t just change people’s way of life, it will help them gain fresh lives.

“Even though the government provides free HIV medicine, many are unable to take the medicine because it needs to be taken with food, and they do not always have food,” Barbosa said.

“Providing jobs will provide income for food,” she said. “Hopefully, this will break the cycle of poverty.”

How to help

All donations go through Ordinary Hero and are then sent to Endihnew Hope.

Ordinary Hero groups travel at least five times per year, and the teams have since been visiting Endihnew’s ministry and working with the women and children.

Donations may be mailed to Ordinary Hero, P.O. Box 1945, Brentwood, TN 37024. Checks to Ordinary Hero should have “Clay Program” in the memo.

People with questions for Barbosa may email Kimberly@ordinaryhero.org. An online link for donations is at ordinaryhero.webconnex.com/entoto.

Saturday, February 8, 2014

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

Ethiopia/AU: Africa must provide enough food for consumption, export (Feature by Anaclet Rwegayura, PANA Correspondent)

Ethiopia/AU: Africa must provide enough food for consumption, export (Feature by Anaclet Rwegayura, PANA Correspondent)

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (PANA) - Africa’s ambition in agriculture, according to the African Union (AU), is to produce enough food to feed its growing population and become a leading exporter of good food.

However, analysts say if the continent is ever to begin a journey toward that goal, the time to do so is now.

While Africa takes pride in its appetising food varieties, it does not produce enough to meet the needs of local consumers and it is yet to capitalise on this resource endowment.

This explains why African leaders have underlined collective actions across the continent focused on improving agricultural planning and policies, scaling up investment and harmonising external support around African-owned agricultural plans.

They have recognised that enhanced agricultural performance is key to growth and poverty reduction through its direct impact on job creation and increasing economic opportunities, especially for women and the bulging youthful population.

Furthermore, improved agriculture would have strong linkages with other activities related to food security and improved nutrition.

As a commodity, food requires processing even for a simple meal. Processing is part and parcel of industrialisation but Africa’s industrial enterprises have largely been weak and inconsistent.

Should Africa keep on exporting raw commodities, food included, when developing countries of other regions are exploiting globalisation by supplying the world market with intermediate and final products?

Since the answer to that poser is surely a resounding no, then it is time this continent set itself on a new path of development that places commodity-based industrialisation at the centre stage.

African soft-commodity (food) processing should open up major possibilities for value addition, but it requires large and resource-intensive interventions to expand and upgrade agricultural output, according to recent studies on the continent’s economic transformation.

In the view of the AU and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), these interventions will create multiple opportunities and economies of scale for developing backward linkages, related to local production of inputs such as fertilisers, small capital equipment and spare parts as well as business support services.

Africa has over the past decade raised the profile of its agriculture through the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP).

“CAADP experience has demonstrated that Africa as a region has a well-crafted, home-grown framework guiding policies, strategies and actions for agricultural development and transformation,” the AU Commission (AUC) maintains.

Through this experience, the Commission has mobilised and aligned multi-stakeholder partnerships and investments around national agriculture and food security investment plans.

In marking 2014 as Africa’s Year of Agriculture and Food Security, the world is anxious to see this continent going the right way to food security.

Political and business leaders as well as cultural activists need to start the right talk with their people about food security, so that together they can address the very real concerns about food production and environmental conservation in their localities.

At the end of the year, each African country should provide believable data, not just about stockpiles of food harvested during this period, but also regarding their score on elimination of cases of underweight children, undernourishment of children and adults – especially expectant mothers – and food price affordability for the general public.

Food producers and marketers now have a good base from which they can expand business beyond national borders, taking into account the youthful population of consumers across the African continent.

Governments need to back their ambitions and endeavours to the hilt, especially in the 34 countries that have signed the CAADP compacts to date.

New investments should be appropriately directed to crops where countries have a comparative advantage in production so that they can fare well in international competition.

“The performance of African agriculture has been encouraging – with annual agricultural GDP growth having averaged nearly 4 per cent since 2003,” said the AUC, adding, “On average public agricultural expenditures have risen by over 7 percent per year across Africa since 2003, nearly doubling public agricultural expenditures since the launch of CAADP.”

This should give African investors searching for yield the incentive and the confidence to vigorously look for more lucrative opportunities in agro-industries.

Success-bound countries should move into higher value added activities of commodity processing, marketing and distribution.

Once firms enter the global value chain, they have to meet very demanding market requirements of price, quality and lead times. Technical standards are crucial when the markets are Europe, the United States or Japan.

The 2013 Economic Report on Africa, jointly published by the ECA and the AU, pointed out that assistance from the firms driving global value chains becomes very important to support local upgrading.

For instance, Kenya’s fresh vegetable exporters and Ghana’s cocoa processors receive support from their global buyers in technical and non-technical areas, yet this is the exception rather than the rule.

A key finding in the report was that regional and domestic markets offer opportunities for value-added products.

Nigerian cocoa processing firms have found regional and domestic markets for confectioneries and beverages. Cameroon’s chocolate manufacturers and Ethiopian roasted coffee firms supply domestic retailers.

Looking for buyers is a costly exercise for any firm but critical for a firm that wants to join a global value chain.

Therefore, economists suggest, local firms attempting to move into higher value added products need government support, as those firms that succeed can provide information and channels for other domestic firms.

-0- PANA AR/SEG 20Jan2014

However, analysts say if the continent is ever to begin a journey toward that goal, the time to do so is now.

While Africa takes pride in its appetising food varieties, it does not produce enough to meet the needs of local consumers and it is yet to capitalise on this resource endowment.

This explains why African leaders have underlined collective actions across the continent focused on improving agricultural planning and policies, scaling up investment and harmonising external support around African-owned agricultural plans.

They have recognised that enhanced agricultural performance is key to growth and poverty reduction through its direct impact on job creation and increasing economic opportunities, especially for women and the bulging youthful population.

Furthermore, improved agriculture would have strong linkages with other activities related to food security and improved nutrition.

As a commodity, food requires processing even for a simple meal. Processing is part and parcel of industrialisation but Africa’s industrial enterprises have largely been weak and inconsistent.

Should Africa keep on exporting raw commodities, food included, when developing countries of other regions are exploiting globalisation by supplying the world market with intermediate and final products?

Since the answer to that poser is surely a resounding no, then it is time this continent set itself on a new path of development that places commodity-based industrialisation at the centre stage.

African soft-commodity (food) processing should open up major possibilities for value addition, but it requires large and resource-intensive interventions to expand and upgrade agricultural output, according to recent studies on the continent’s economic transformation.

In the view of the AU and the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA), these interventions will create multiple opportunities and economies of scale for developing backward linkages, related to local production of inputs such as fertilisers, small capital equipment and spare parts as well as business support services.

Africa has over the past decade raised the profile of its agriculture through the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP).

“CAADP experience has demonstrated that Africa as a region has a well-crafted, home-grown framework guiding policies, strategies and actions for agricultural development and transformation,” the AU Commission (AUC) maintains.

Through this experience, the Commission has mobilised and aligned multi-stakeholder partnerships and investments around national agriculture and food security investment plans.

In marking 2014 as Africa’s Year of Agriculture and Food Security, the world is anxious to see this continent going the right way to food security.

Political and business leaders as well as cultural activists need to start the right talk with their people about food security, so that together they can address the very real concerns about food production and environmental conservation in their localities.

At the end of the year, each African country should provide believable data, not just about stockpiles of food harvested during this period, but also regarding their score on elimination of cases of underweight children, undernourishment of children and adults – especially expectant mothers – and food price affordability for the general public.

Food producers and marketers now have a good base from which they can expand business beyond national borders, taking into account the youthful population of consumers across the African continent.

Governments need to back their ambitions and endeavours to the hilt, especially in the 34 countries that have signed the CAADP compacts to date.

New investments should be appropriately directed to crops where countries have a comparative advantage in production so that they can fare well in international competition.

“The performance of African agriculture has been encouraging – with annual agricultural GDP growth having averaged nearly 4 per cent since 2003,” said the AUC, adding, “On average public agricultural expenditures have risen by over 7 percent per year across Africa since 2003, nearly doubling public agricultural expenditures since the launch of CAADP.”

This should give African investors searching for yield the incentive and the confidence to vigorously look for more lucrative opportunities in agro-industries.

Success-bound countries should move into higher value added activities of commodity processing, marketing and distribution.

Once firms enter the global value chain, they have to meet very demanding market requirements of price, quality and lead times. Technical standards are crucial when the markets are Europe, the United States or Japan.

The 2013 Economic Report on Africa, jointly published by the ECA and the AU, pointed out that assistance from the firms driving global value chains becomes very important to support local upgrading.

For instance, Kenya’s fresh vegetable exporters and Ghana’s cocoa processors receive support from their global buyers in technical and non-technical areas, yet this is the exception rather than the rule.

A key finding in the report was that regional and domestic markets offer opportunities for value-added products.

Nigerian cocoa processing firms have found regional and domestic markets for confectioneries and beverages. Cameroon’s chocolate manufacturers and Ethiopian roasted coffee firms supply domestic retailers.

Looking for buyers is a costly exercise for any firm but critical for a firm that wants to join a global value chain.

Therefore, economists suggest, local firms attempting to move into higher value added products need government support, as those firms that succeed can provide information and channels for other domestic firms.

-0- PANA AR/SEG 20Jan2014

Monday, November 4, 2013

Forget feast or famine, it's time to tell the complex story of development | Global Development Professionals Network | Guardian Professional

NGO communicators, like the wider PR industry, seem more interested in innovating content delivery rather than content itself

- 42

- 12

David Humphries

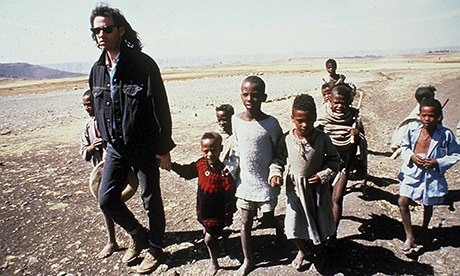

Singer Bob Geldof in Ethiopia. Pictures of starving children have been a staple since the Ethiopian famine of 1983 to 85. Photograph: TODAY / Rex Features

If the first casualty of war is truth, the first casualty of a disaster situation is complexity.

A few years ago, I had a conversation with a New York Times journalist who complained that NGOs had represented the situation in Haiti too simply and optimistically. No one, for example, had brought up land tenure, which quickly revealed itself to be one of the major challenges understood by few in the post-earthquake confusion. I pointed out that my organisation, Global Communities, had spoken about land tenure almost immediately – but nobody listened. Instead, the media focused on stories of desperate chaos or children miraculously pulled from rubble. We agreed that poor reportage is a hungry mouth that both sides feed. But there is no point in complaining about journalistic practices until we,communications professionals, first examine our own.

This applies to how we present natural disasters like the Haiti earthquake and protracted human disasters like Syria. It also applies to long-term poverty, and how we represent entire continents such as Africa or South America. So how do we better communicate the complex conditions in the developing world, which so few people see for themselves? And why do so few organisations even attempt to communicate complexity?

Traditionally, NGOs vacillate between guilt and hope in their communications. Pictures of starving children have been a staple since the Ethiopian famine of 1983 to 85. In the past decade, however, guilt has taken a back seat and instead, we are bombarded with carefully chosen images of success and productivity. We hear stories of microfinance lifting people out of poverty or, with the new philanthropy of the dotcom entrepreneurs, the transformative power of text messaging and Twitter. These methods of communication are driven by the need to raise funds for genuinely vital work. But they don't show the full picture. After all, a story of someone's life changed by a loan can be rapidly reversed when their house in a slum is bulldozed or their family member dies because they didn't have adequate healthcare.

What we are selling is old and tired. And it isn't working: overall funding for global development organisations is decreasing internationally; NGOs have been struggling to counter criticism of microfinance; the earthquake in Haiti has inspired a whole industry of NGO criticism; and traditional attempts in the US to raise funds for humanitarian work in Syria are failing in the light of an increasingly complex crisis. We are underestimating our audience.

We know that innovation is the key to new sales, and as an industry we are always talking about innovation. So why not be innovative and communicate openly the multifaceted issues facing the developing world? Why not let the new voices from the global south speak? Where is the disconnect between what we do and see, and what and how we communicate?

Part of the problem lies with the communications industry. It is driven by the need to sell, and is measured in web hits and social media shares. But increasingly the focus is not on content creation but the medium for the content. The PR industry, for example, publishes endless articles on the best vehicles for delivering your content – social media, traditional media, owned media – but rarely on the actual content. Similarly, the communications industry has mistakenly focused on innovative methods of content delivery, while totally ignoring innovative content. A stale message in a press release is just as stale on Twitter.

Meanwhile, the global development discourses rarely penetrate communications departments, not least because they are written in impenetrable pseudo-academic jargon, what the Economist memorably coined "NGOish." We have to work with development professionals to unpack their linguistic horrors of value chains, gender mainstreaming and capacity building to find out what that actually means and then communicate it effectively.

Then there is also control and convenience. On each side of the Atlantic respectively, it is the same big brands, the same talking heads, and the same messages that are repeated. Journalists know where they can call to get a rent-a-quote for their article and it is usually from within the same time zone. Even though there are thousands of articulate global development professionals from emerging economies on our staff, big brands demand on-message speakers, trained for the western media: put on a new voice and they might not say what you want them to say. Control and convenience outweigh conviction.

The status quo is not good enough. NGOs are increasingly concerned about their relevance in the future and are examining their business models, and rightly so. Communications professionals need to take a lead role in this. Good media coverage and honest examination of complex issues are not mutually exclusive. Yale's Innovations for Poverty Action has succeeded in bringing complex issues in aid and development to the forefront of global development media coverage. Most of my own organisation's greatest communications successes have been based around complex issues such as urban disasters and allowing voices from the global south to speak about their own situation.

As long as poverty exists, so too should NGOs. But until we acknowledge that the solutions to poverty are complex and begin communicating them as such, we will appear increasingly irrelevant. What we are communicating is not working. Let's move beyond guilt and optimism and try something new – complex and sometimes troubling reality.

David Humphries is director of global communications for Global Communities.

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. To get more articles like this direct to your inbox, sign up free to become a member of the Global Development Professionals Network

Tuesday, October 15, 2013

Friday, October 4, 2013

New book examines legacy of media coverage of Ethiopia's 1984 famine

Irish rock star Bob Geldof (C) helps people at a feeding centre in Lalibela, 700km from the capital Addis Ababa, Ethiopia in May 2003. REUTERS/Antony Njuguna

LONDON (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – It is almost 30 years since a single TV news report alerted the world to a massive humanitarian emergency unfolding in Ethiopia.

"Dawn, and as the sun breaks through the piercing chill of night on the plain outside Korem, it lights up a biblical famine, now, in the 20th century. This place, say workers here, is the closest thing to hell on earth," the piece began.

Accompanied by shots of thousands of starving people arriving at feeding stations in northern Ethiopia, the report by the BBC's Michael Buerk triggered an outpouring of donations and one of the biggest humanitarian efforts the world had ever seen.

It spawned Live Aid, the concert organised by pop star Bob Geldof, and heralded an era of celebrity do good-ism, which is now practically inescapable. It also led to the unprecedented growth of foreign relief organisations, changed the face of NGO fundraising and helped cement Africa's image as a continent of plagues, pestilence and suffering that continues until today.

In the minds of many, the reporting of the famine and the subsequent humanitarian effort were a huge success. Yet, a new book by former BBC journalist-turned-academic Suzanne Franks shows the opposite to be true.

"Reporting disasters: Famine, aid, politics and the media" takes a comprehensive look at the iconic news event. Mining BBC and government archives, it concludes that media coverage of the crisis was misleading and inaccurate, and that the aid effort ultimately did more harm than good.

"What made it really interesting ... is that many people have wonderful intentions but ... despite these good intentions, there are terrible outcomes," Franks told Thomson Reuters Foundation. "That is very difficult to understand."

Although few would deny the power of Buerk's report and the profound impact it had, Franks' research dispels any notion that media coverage of the famine had any lasting effect on British policy towards Ethiopia, considered by London and Washington to be a "distasteful regime" and a client of the Soviet Union.

In reality, hardly any new money was provided by then prime minister Margaret Thatcher's government largely because, as Franks points out, Thatcher's attitude to aid was said to mirror on a global scale her suspicion of the welfare state at home.

Besides analysing the response to the famine, Franks also tells the story behind the story, explaining why it became such a hit. Buerk's fortuitous lift on a World Vision plane to Korem, a strike by a rival TV station, a quiet news period and record European grain surpluses at the time all ensured the story was told, and told to maximum effect.

From the outset, the famine was characterised as a sudden event caused by drought. But the warning signs were known by the British government long before Buerk's report was broadcast, reinforcing what we now know about hunger crises – that they are a long time in the making.

Media reporting also ignored the obvious role politics played in creating the conditions for famine – how starvation had become a useful weapon of war in dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam's battle against insurgents in the north, and the extent to which the fighting was causing problems with food supply.

Not only was food aid diverted by both government and rebel forces but so too were many of the trucks used to distribute relief supplies. That, and the foreign currency brought in by aid agencies, inadvertently helped the conflict to continue.

In hindsight, it's easy to see why within a few years of Buerk's report being aired on Oct 23, 1984, there were yet more appeals for funds to fight hunger in Ethiopia, despite millions of dollars already raised.

Even worse, donations helped aid agencies set up feeding centres that were used by government officials to round up unsuspecting Ethiopians for resettlement hundreds of miles away from rebel areas.

The impulse to tell a simple story, unmuddied by complexity and doubt, is shared by the media and aid industry alike, Franks says.

"We all want the narrative of the goodie versus the baddie in a nice clear-cut story," she said. "But if you try and tell the real story, which is probably three different baddies all fighting each other and nobody coming out of this very well, how sympathetic is your hearing going to be? And how much are you really going to be able to raise money and get sympathetic attention based on that?"

This aversion to telling the whole story leads Franks to the sad conclusion that "despite all the noise, there was ultimately little wider understanding of the fundamental long-term causes and the real nature of the famine".

Little has changed in the media reporting of famines in the years since the Ethiopian crisis, Franks said. Citing Somalia's famine in 2011, she said there were a few but not many journalists willing to tell the "horrible and complicated story" of why people were starving in the Horn of Africa country which was, at the time, mainly controlled by al Shabab militants.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)